By Arne K. Lang

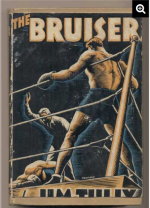

Summertime is reading season. In olden days when the leading Sunday papers had a separate book review section and vacationers carried books in their carry-ons, the advent of summer unleashed a flurry of enthusiastic book reviews. In this spirit, let us submit Jim Tullys’ novel “The Bruiser” for your consideration. It’s an old book, first published in 1936, but as a panorama of the prize ring -- warts and all – it stands up well if you like your fiction with a lot of pulp.

The protagonist is Shane “Wildcat” Rory who claws his way out of hobo jungles to become the heavyweight champion of the world. True, that sounds like a hackneyed Hollywood “B” movie and the comparison is fair, but the book is also chock-full of insights that could have only come from the pen of a man that had been immersed in the prizefighting subculture.

About The Author

The son of a ditchdigger who came from Ireland at the age of 10, Jim Tully was born in 1886 in St. Marys, a former Indian trading post in Western Ohio. Jim’s mother died when he was five and he was sent to a Catholic orphanage in Cincinnati. He left there at the age of 11 to work on a farm and then, while still in his mid-teens, he took to wandering about the country, picking up odd jobs here and there. When he hopped a freight, whatever money he had was sewed into different parts of his clothing. In the hobo jungles, his pals called him Cincinnati Red.

Tully’s formal education stopped when he left the orphanage, but he was an inveterate reader who spent many hours in public libraries. He was never comfortable with the term “hobo” -- folks used it interchangeably with the word “bum” – and in his reminiscences of those days insisted on identifying himself as a “road-kid,” his term for an adventurous vagabond.

In Kent, Ohio, where Tully set down roots for a while, he found employment working over a blast furnace in a factory that made chains of the sort that one might find attached to the anchor of a boat. Kent is near Akron where Tully had his first documented prizefight. Lore has it that he heeded the call for a volunteer when one of the boxers on the card was a no-show. Many professional boxing careers actually started this way.

An article in the Philadelphia Inquirer said Tully had 30 pro fights. Boxrec has been able to document only three, the first in 1909 on a card that featured future Hall of Famer Johnny Kilbane, and the last in 1914. The true count is probably somewhere in the middle. In those days, outside the biggest cities, many papers didn’t publish on Sundays and, if they did, the paper was put to bed early. A Saturday night boxing show went off too late to make the cut and by Monday, unless one or more of the combatants had a big local following, it had lost its news-worthiness. Fights in the hinterland that made the national news wire rarely included anything about the undercard.

The hero of “The Bruiser” matures into a heavyweight, but Jim Tully, five-foot-three and stocky, was likely in the junior lightweight class. With a mound of red hair straggled in all directions, he looked like many fighters of the period when the great majority of white boxers were Irish. Photographs of Tully as a young man call to mind Mickey Walker, the original Toy Bulldog.

[caption id="attachment_72945" align="alignnone" width="211"]

The Book

“The Bruiser” opens on a miserably wet night in a railroad yard. Rory, then eighteen years old, crosses paths with a black boy of about the same age who has just competed in a battle royal. They repair to a saloon before going their separate ways. The boy has adopted the ring name Torpedo Jones and he turns up again later in the book as an opponent that Rory must defeat to earn a shot at the champion.

Shane Rory’s manager, Silent Tim Haney, is a stock character in boxing fiction, a wizened ex-pugilist who knows all the tricks of the trade. Silent Tim’s great ambition is to take a raw fighter and build him into a heavyweight champion. He had been close on two previous occasions, near-misses that taught him that maneuvering a fighter into a world title is a process “more delicate than assembling a watch.”

In an earlier day, Silent Tim had managed Jerry Wayne. In his prime, Wayne had been a great ring artist: “He’d move in the ring like he had wings on his shoulders and ball bearings on his feet.” But he had taken too many punches and gone “slug-nutty.” (The Jerry Wayne character is plainly based on former lightweight champion Ad Wolgast with whom author Tully purportedly sparred. Wolgast was in and out of sanitariums before he had his final fight and spent the last twenty-eight years of his life locked up in a California insane asylum where he spent his waking hours plotting his comeback.)

When Rory visits Jerry Wayne in the institution where he has been locked away, it preys on his mind and it impacts his performance in his next fight, a loss that sends him back to the drawing board. The fear of winding up like Wayne or like Gunner Maley, another character in the book – “walking on his heels up and down North Clark Street, punchin’ shadows” – impels Rory to eventually walk away from boxing in the fashion of Gene Tunney, at the pinnacle of his hard trade with a wholesome girl by his side and with all of his faculties intact. (Tully reportedly wanted a grittier, less formulaic ending but was overruled by his publisher.)

“The Bruiser,” Tully’s eleventh book, was dedicated to “my fellow road-kid Jack Dempsey.” Tully, who wrote dozens of profiles of famous people for serious publications and for cheap Hollywood fan magazines, had written a profile of Dempsey for a 1933 issue of American Mercury and would include a profile of the Manassa Mauler in his final book, “A Dozen of One,” portraits of 13 well-known people including the boxer Henry Armstrong and the fabulous raconteur Wilson Mizner who once owned a piece of Stanley Ketchel, the fabled Michigan Assassin.

Tully wrote for the masses but his admirers included many writers whose bent was more highbrow, notably H.L. Mencken, the sage of Baltimore, but also Langston Hughes who introduced Tully to “Hammerin’” Henry Armstrong, and Gerald Early whose 1994 book, “The Culture of Bruising: Essays on Prizefighting, Literature, and Modern American Culture,” received a National Book Award.

Early wrote the foreword to the 2010 reissue of “The Bruiser” from Kent University Press. He had this to say regarding Jim Tully: “Few novelists captured the contradictions of his country so simply or so honestly in the metaphor of the pure, fatalistic, and merciless community of bruising. His work deserves to be rediscovered.”

The reissue was the handiwork of Mark Dawidziak, a TV critic for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and Paul J. Bauer, a Kent, Ohio, book dealer who were busy co-authoring a biography of Tully. The book, titled “Jim Tully: American Writer, Irish Rover, and Hollywood Brawler,” also published by Kent University Press and with a foreword by Ken Burns, was released in 2011.

Jim Tully had developed Parkinson’s disease when he died in 1947 at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles at age sixty-one.

Arne K. Lang’s latest book, titled “George Dixon, Terry McGovern and the Culture of Boxing in America, 1890-1910,” will shortly roll off the press. The book, published by McFarland, can be pre-ordered directly from the publisher (https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/c...-little-giants) or via Amazon.

Last edited: